“Content provenance” is an emerging set of techniques that Hypha has been working with, often in the context of mis/disinformation. Instead of asking “Is this content fake?” content provenance systems ask a narrow, more technically precise question: “Where did this come from, and what happened to it?” By cryptographically binding media to devices, creators, and workflows, provenance turns content into an auditable object.

Origins of provenance

In the period after World War II, there was an explosion of published writing, particularly in science and engineering. People were worried that there would be so much information that we would be too overwhelmed to make sense of it. (Perhaps similar to our fears surrounding the deluge of AI driven content)

In 1953, Hans Peter Luhn, a printer and textile expert, hired at IBM as an “inventor”, proposed a technique that we now understand as one of the first practical hash functions. He was trying to solve the specific problem of quickly looking up a phone number in a large phone book. Instead of searching through the list of phone numbers sequentially, item by item, number by number, he wondered if there was a calculation you could perform to know where the item would be instantly.

Luhn suggested putting the phone numbers into “buckets.” Given a phone number, the computer would perform a quick calculation to determine which bucket it belonged in, then search only that bucket. This was a very early hash function: a mathematical process that transforms data (in Luhn’s case, a phone number) into a unique fingerprint (the bucket).

Run the same data through a hash function, you always get the same result. Change even one bit, and you get a completely different result. Today’s content provenance systems use this same property of hashing to uniquely identify content and detect tampering. If a file’s hash changes, the file must have been changed. We can ensure the integrity of the file.

Hash functions can help prove that a file’s contents haven’t changed, but how do we prove who created the file in the first place? This is the problem of authentication, and it’s solved using digital signatures, an application of public key cryptography.

Public key cryptography is a set up with two keys. A creator uses a “private key” (think of it as a secret stamp) to sign a file. Anyone can then use a “public key” to verify that the stamp is authentic. The principle is straightforward: create something that’s computationally expensive to forge but cheap to verify.

We’ve always relied on forgery cost as the barrier to authentication. The Ottoman Sultans used the Tughra, an intricate calligraphic monogram, to authenticate imperial decrees. It worked because forging it required specialized craftsmanship, years of training, and access to specific materials. The cost of creating a convincing fake was cost prohibitive. Today, we use digital signatures to do the same thing, just with cryptography instead of calligraphy. You could use a powerful computer to forge a digital signature, but that computer would need to be tremendously more powerful than any computer humans have ever built.

So: hashes prove content integrity. Digital signatures prove authorship. Content provenance combines these to prove chain of custody, authenticating every entity that touched the content and ensuring its integrity across the chain.

Provenance in practice

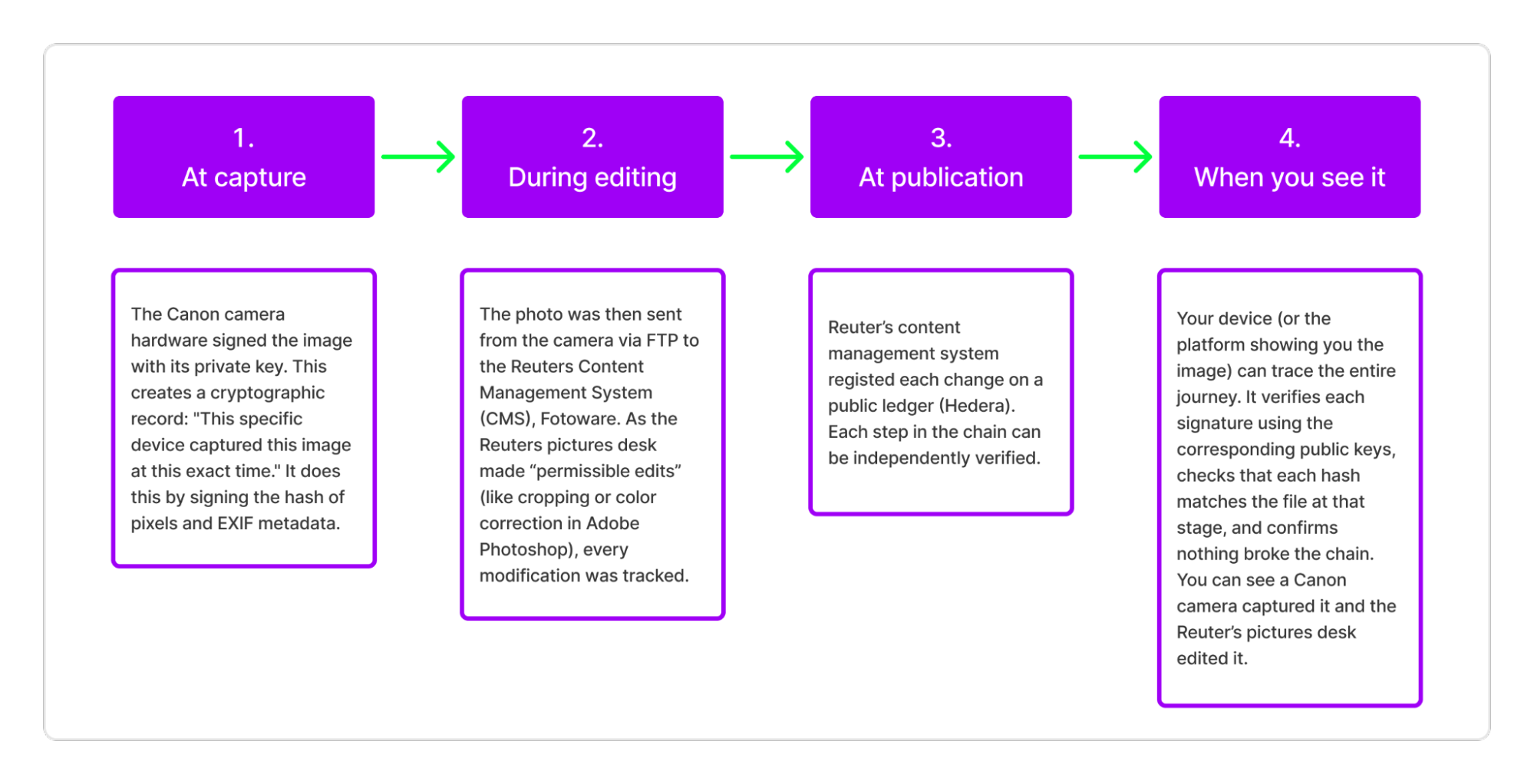

Hypha members at Starling Lab, worked with Reuters and the camera manufacturing company, Canon, to demonstrate the provenance workflow in the field. This end-to-end system was field-tested by Reuters photojournalist Violeta Santos Moura in Ukraine during March and April of 2023.

The most prominent framework trying to standardize the provenance process is called C2PA (the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity). As of 2026, we’re seeing real adoption, with cameras (Sony, Canon, Leica), software (Photoshop, Premiere), platforms (Google, Meta, Microsoft, OpenAI), and news organizations (BBC, Bloomberg), engaging with the standard.

That matters, because provenance only works if it survives across tools, workflows, and platforms. Without shared standards, provenance data would be stripped, ignored, or inconsistently applied. With them, it has a chance to become infrastructure rather than a niche feature.

A key feature of C2PA is that it allows for provenance information to travel with the content itself in the form of signed metadata. It doesn’t require another database to store information about the provenance, rather the content comes bundled with the provenance information. This is particularly valuable when publishers do not have a priori knowledge of how or where their content will be viewed.

Limitations

Content provenance raises the cost of certain deceptions. It makes it harder to claim videos are AI-generated when they’re not. It creates audit trails journalists can follow. However, it does not mean that the content is accurate or truthful. We think of it purely as infrastructure.

And the infrastructure itself could have vulnerabilities. Who decides which public keys are trustworthy? We rely on Certificate Authorities (like DigiCert or Let’s Encrypt) that vouch for identity. If compromised or coerced, the entire chain collapses. In 2011, hackers breached DigiNotar and obtained fraudulent certificates to impersonate Google, enabling surveillance of Iranian citizens.

Then there’s the privacy paradox. If you’re a journalist in Belarus documenting protests and your phone signs every photo, that signature becomes evidence against you. There are techniques (like Zero Knowledge proofs) for proving “this photo is authentic” without disclosing “I took this at these coordinates”, but implementing this is complex and many tools don’t support it yet.

Our greatest concern around provenance is that we could move from a world of “fake content” to a world of “signed (mis)information”. The technical authenticity of media can be a shield for dishonest narratives.

Here are some scenarios to consider:

A politician gives a speech. It’s recorded with a signed camera, full C2PA credentials. In context, they’re presenting an opponent’s argument before refuting it. But a verified account shares a 15-second clip (cryptographically authentic, completely signed) that only includes the inflammatory quote. The provenance is perfect. The story is a lie.

Or: a protest organizer gets photographed by a professional camera with full Content Credentials. That genuine image then gets shared with a caption claiming the person is a paid agitator. The photo is real. The accusation is false.

Perhaps the most insidious form of misinformation is reality stripped of context or paired with false narratives. Technology can solve the problem of revealing provenance. It doesn’t solve the interpretation problem, the context problem, or the intent problem.

This is not to say that provenance technology is useless. It is, like any other technology, limited in scope.

Who is provenance for?

At Hypha, we believe that our informational landscape is going through a period of massive change, leading to an epistemic crisis. There are a host of intersecting factors here: the relationship between reader and publisher being severed, increasingly mediated by big tech platforms (first social media and now big AI); user generated content providing faster information and surfacing underreported views from the margins; outmoded media business models, kept alive by private benefactors or through state intervention; and now generative AI exacerbating the liar’s dividend, where the mere existence of deepfakes allows dishonest actors to dismiss genuine, damaging evidence as “AI-generated.”

This problem space is complex and requires social and political interventions, but also needs a rearchitecture in our technical systems. At Hypha, we’re researching using open web protocols to rebuild connection with users, thoughtful and values-oriented ways of using AI for knowledge management and synthesis, and content provenance, the topic we’re covering here. We’ll be writing more on the former in future posts in our digital trust series.

Here’s how different actors should think about content provenance today:

Publishers

- Your content isn’t being surfaced just on your channel anymore. It’s being pulled up by LLMs, summarized by AI systems, shared and remixed across platforms. Laying down provenance infrastructure now means you can trace where your content goes. This could enable attribution and potentially monetization as the business models around AI-era content licensing develop.

- Your authentic content is being misused right now. Photos taken out of context, videos clipped to misrepresent events, genuine footage dismissed as AI-generated. Provenance gives you technical proof: capture device, timestamp, chain of custody. This can be useful evidence in court and for takedown requests when others misuse your content.

- Content provenance technology is still nascent. Currently most content on the web is unsigned. Early adopters can start “showing their work” to rebuild trust with their audiences and differentiate through their accountability.

Platforms

- Provenance gives you another signal for trust and safety work. Coordinated inauthentic behavior often involves rapid content creation and distribution. Signed content with verifiable chains of custody is harder to generate at scale.

- Provenance creates a rich space for product innovation: new ways of monetization and novel social interactions. Look at current trends around remixing (TikTok duets, quote tweets, response videos, meme templates): provenance allows you to trace the evolution of content.

Web users

- Use provenance to verify information. Content provenance shifts epistemic authority from “what looks real” to “who controls the keys.” It changes the terms of the debate, because those who control the keys are the ones that should be held to account. When you see content and you’re asking yourself “is this real,” you know who to ask for evidence.

Further reading

- How Hypha has been supporting journalists to prove content authenticity and integrity when the stakes are high: Hypha at Starling Lab

- How Hypha built the data processing pipeline for a metadata database: Storing metadata at Starling Lab

- Hypha has been helping Streamplace (a video streaming platform on ATproto) develop a signed metadata standard. Read their docs

- This Bluesky thread by Eliot Higgins from Bellingcat captures much of Hypha’s views on our information landscape: Eliot Higgins on Bluesky

- C2PA explainer

- IEEE biography on Luhn’s work