Over the holiday break, I headed to Vancouver Island where I was born and raised to spend the holidays with my extended family. And while I didn’t bring my laptop, I did take a copy of Empire of AI so that I could finish it while eating Christmas cookies and relaxing. Despite not being your usual vacation read, it’s a great book and recommended for anyone curious about the current arc of AI and how decisions, especially technical decisions, by OpenAI have shaped our current trajectory. (It’s also got some good gossipy bits about the OpenAI leadership, if you enjoy that sort of thing.)

While the book delves into frontier models, at Hypha we’ve been exploring the world of open source AI and thinking through the state of cooperative AI (as in, AI that’s developed by or for cooperatives). While I appreciate there is a significant amount of ideological handwringing in the cooperative sector over the replacement and deskilling of workers, this all the more reason for people with varied motivations to build and offer products that focus on more than just profit. It seems unlikely that AI is going to disappear from our workplaces, or disentangle from the code running the platforms and tools we use in our personal lives. So short of a fulsome rejection of digital technologies, which may be an option for some people but not all, I’m advocating for thoughtful approaches to AI in worker-owned organizations. Weaving responsibly-built AI into cooperative workflows need not replace workers, and there is potential for time savings for administrative and operational tasks. While I’m generally wary of ‘efficiencies and effectiveness’ rhetoric, within the cooperative context in which members can exercise control over the outcomes of doing work faster, the possibilities are more interesting. Cooperatives could decide to move to a four-day work week, for example. Or refocus their work, emphasizing solidarity or care. Each use case would be context specific, and would require thoughtful experimentation. The point is to be creative about how we use technology, not doctrinaire.

Late last year, my fellow Hypha member Vincent and I travelled to the Platform Cooperative Consortium’s annual conference, with a mission to find more examples of cooperative AI projects. Held in Istanbul under the simple title of Cooperative AI, the conference was a great gathering–big enough that there was a breadth of opinions and presentations, but small enough that you could meet most attendees and connect with them in a meaningful way (i.e. not just the usual inane small talk). Co-organizer Trebor Scholz posted a good recap of the event here, and Miles Hadfield wrote a very comprehensive article here. My biggest takeaway from the conference was the need to see more cooperative AI use-cases out in the wild. While I was impressed by the diverse perspectives of the participants, I came away wanting more experiments, more in-the-code examples of what cooperative AI might look like, not as an academic discussion but as many attempts – large, small, successful and not – and visions of what artificial intelligence could be. Imagine housing co-ops deploying automated tools for predictive maintenance and repair, or platform-based personal support worker co-ops integrating scheduling optimization that respects worker preferences and accounts for client needs.

“resisting Big Tech’s extractive dominance means connecting the already-emerging pieces of a Solidarity Stack—cooperative data centers, AI cooperatives, federated infrastructures, tech cooperatives, and small LLMs—so that these efforts remain locally anchored while building on shared, federated digital infrastructure linking communities globally.” –Trebor Scholz

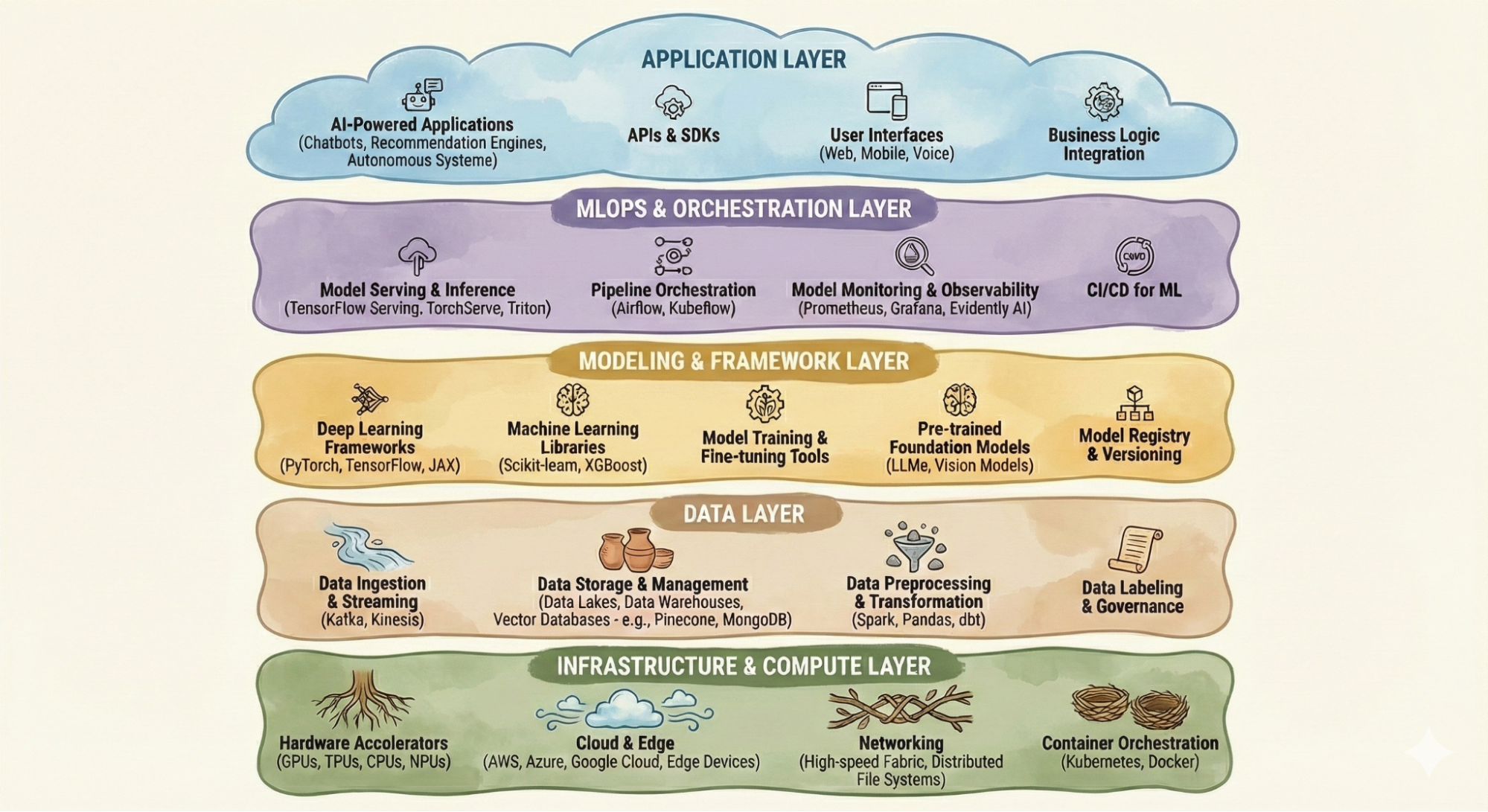

Fellow conference attendee Melissa Torres, a member of READ Coop, which stewards the AI transcription Transkribus project, noted that she wasn’t aware of any other co-operatively governed AI initiatives. Torres assumes that start-up funding is a major reason for this (Transkribus was bootstrapped with a large grant from the European Commission), but also because Transkribus’ domain, handwriting recognition for cultural heritage, hits a sweet spot of being both widely useful and focused, with a ready community of librarians, archivists, volunteers willing to contribute their labour over many years. I know of other cooperatives that have an AI- focus, but Transkribus is unique in that it has developed its own LLM; in other words, it’s operating at multiple points at the technical stack. Riffing on Scholz’s idea of the solidarity stack, what is the potential for other interventions to counter current AI trends?

While there are possibilities inherent throughout the stack, I’m going to focus here on the application, data and infrastructure layers as points of cooperative intervention; partially because I’m the most familiar with these layers technically but also because I can see the cooperative potentially most clearly. Stats on global tech cooperatives are hard to find, but we know they are out there (Hypha being a case in point). If just a fraction of these organizations began to explore the potential of local or on-premise AI, and iterated to offer services and products based on open weight or even open source models, that would be an excellent start. Our RooLLM project is Hypha’s overture in this direction, fueled by questions about data privacy and security, and the use of Big AI chat clients like ChatGPT and Claude. For our friends in the global south, advances in on-device AI should be particularly interesting (and perhaps particularly concerning, given the state of the Apple versus Google mobile phone duopoly).

Apart from tech cooperatives developing applications for automation and similar uses, I can also see how the sector as a whole could benefit. A lack of awareness and educational materials–especially in the context of business schools–is a well-known problem amongst cooperative developers and sector leaders. Developing AI applications to demystify how one starts a cooperative and to answer commonly asked questions would be one starting point. Last year, we prototyped a bylaw generator; essentially just a prompting tool for co-op founders. (Drop us a note if you’re curious about how it works and want to test it out!)

Moving from the application to the data layer, and a number of potential interventions come to mind. Data cooperatives, which are member-owned organizations that pool personal data to control its use and share in any benefits, have gotten a fair amount of airtime in recent years (e.g. this Project Liberty report, which Hypha members contributed to!) but the real-world examples are sparse. This is a huge topic, but briefly, the main challenges to actualizing a data cooperative is lack of initial capital, regulatory compliance issues regarding PII or people-related data in general, and a host of technical interoperability and governance challenges. It’s also a question of incentives; when all you need to do is click a button to trade data surveillance for the ‘free’ use of email, social networking tools etc., why complicate things?

But we (might) be entering an era where private enterprise data becomes increasingly valuable; Epoch AI suggests that we’re only a few years away from LLMs consuming all available public data. If this is indeed the case, then cooperatives, especially large producer or agricultural cooperatives, might want to consider commoditizing their data and selling it to AI companies (in fact, some are already entering into AI-related partnerships). And by using a data cooperative framework to do this, they could generate income for their membership as well. In this future scenario, cooperatives’ values of democratic oversight, accountability, and collective governance map well to managing members’ data and ideally, distributing the financial upside considerably more evenly.

We estimate the stock of human-generated public text at around 300 trillion tokens. If trends continue, language models will fully utilize this stock between 2026 and 2032, or even earlier if intensely overtrained. –Epoch AI

Lastly, on the subject of data: how might workers who perform reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) used to train LLMs agitate for a cooperative approach to their work? Many of these people labour under horrendous conditions and while unionization is clearly a much-needed step, a cooperative model might also return some equity to these important and largely overlooked workers.

Turning now to the layer of infrastructure and compute. AI, like all digital technologies, consumes resources to make the digital ‘magic’ happen. While there is a significant amount of disagreement about AI energy and water consumption– a situation owing largely to the unwillingness of Big Tech to release meaningful data about said consumption–what is known and (is fairly uncontroversial) is that data centres are built in rural areas or in the global south, with benefits flowing to multinational corporations rather than local populations (see also Chapter 9 in Empire of AI). Monopolies and geographic inequity are the hallmarks of current global AI infrastructure, and here cooperatives offer two potential remedies. Firstly, forming cooperatively-run data centres would ensure that more of the economic value stays within the community, with profits flowing back to residents rather than out of the country to foreign owners. Secondly, there is an interesting case to be made for deciding how compute capacity would be allocated e.g. prioritizing local businesses and education initiatives, and then offering the surplus to other customers. This could help foster an ecosystem of local start-ups or support existing businesses that could use these services. Funding an initiative such as Servers.coop, which is focused primarily on software, and wrapping in a responsible AI thread might be a place to start. (On the subject of data centres, I have to give a shout out to this amazing Datascapes project!)

Data centres built with community in mind, where developers go beyond token engagement, seems like a far-fetched idea in our current economic paradigm. But rural electricity cooperatives in the US show us that infrastructure and cooperatives can be intertwined. In case you’re not familiar with these, the tl;dr is that in the 1930s, for-profit electrical companies were not incentivized to provide electrical infrastructure to rural areas (lots of infra for little return). To fill this gap, the federal government under FDR created the Rural Electrification Act of 1936, which helped communities build their own electric grids. As of 2023, there were “831 electric distribution cooperatives serv[ing] 42 million people across the United States.” While there are numerous issues with the electric co-ops, not the least of which being their heavy reliance on coal powered plants, they do offer an interesting template to work from when considering how cooperatives might meaningfully enter the AI infrastructure space. In fact, some of these existing cooperatives could be a starting point; moving from electricity to providing other utilities isn’t too abstract as proved by the New Hampshire Electric Coop, which currently offers broadband service to its members. Bundling digital services and community benefits alongside the development of a data centre–such as mandating local fibre deployment or technical training programs–would also meet a cooperative’s goals of enriching their local communities.

Cooperatively-run infrastructure ties to two related points: digital sovereignty (which we’ve been thinking about a lot at Hypha and will go into in future posts), and the idea of Public AI. There are a couple of complementary but differing conceptions of public AI to consider; the Public AI Network and the Mozilla Foundation’s Public AI are two of the best known. Both offer a vision of AI conceived as a public good, with broad accountability, and public access. ‘Public’ here means some form of government funding, but rather than adding another arms length agency (similar to the IndiaAI model) why not provide funding to member-owned, community-based AI infrastructure? It’s an idea worth exploring given the high stakes, both environmental and societal. I’d love to see the cooperative sector engage with the idea of Public AI and consider how the inherent democracy of co-ops can flavour public goods and enhance accountability–especially where data is concerned.

It’s 2026 and we are living in strange and uncertain times. The current technological paradigm is not working for many people, and while it’s unclear if cooperatively developed, responsible AI can positively bend the arc, we owe it to ourselves to try.