Part 2 of our P2P Primer

In the second part of our series on peer to peer (P2P) protocols, Mauve explores the data models and mutability of Bittorrent, Interplanetary Film System (IPFS), Hypercore and Secure Scuttlebutt (SSB). Read part 1 here, where you can also find the TL:DR comparison chart and grading.

Data Models Overview

If you’re dreaming of publishing data or building an application that adds data, you’ll want to dig a bit more into the data models of these protocols to see what might work best for you. A few things to consider when assessing the options are how often data is changed, how big your datasets are, how much data is shared between datasets, and how you want to access the data from disk.

Data Model - BitTorrent

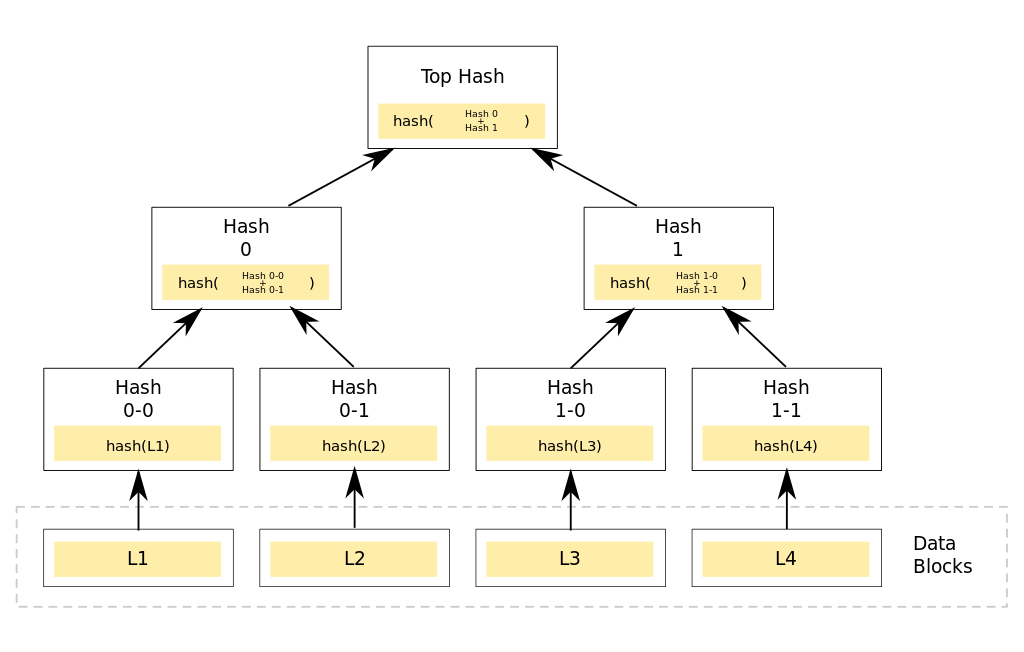

BitTorrent is great at making peer to peer (P2P) file transfer “just work” simply and easily. Its data model is based on a concept called “Content Addressability” where the data inside a torrent gets put through a hash function, which generates a unique value based on the content. If you have the hash of some data, you can verify whether data from another peer is valid by checking if it hashes to the same value. If even a single byte of the data is different from the original, the hash will be different and you can ignore the data from the peer.

Instead of hashing the entirety of the data at once, BitTorrent splits up the files and folders in the torrent into a tree of “nodes’’ that link to each other using hashes for IDs. This is called a Merkle DAG (Directed Asyclyc Graph) or Merkle Tree. The files themselves are split into chunks of a few kilobytes or megabytes in size and added as their own subtree within the Merkle DAG. This is what enables a torrent client to download small bits of files from multiple peers at once and verify their data independently rather than needing to load an entire file before verifying it.

A torrent is then identified by the top-most hash in the tree, called the infohash, which is stored within the Bittorrent magnet link. A .torrent file will contain some metadata about a torrent along with the Merkle tree for the files and folders (without having the actual file data) that can be used to verify data. This also means that, by default, if two torrents contain the same chunk of data they won’t be able to share peers. One outcome of this structure is that torrents are Immutable, and in order to change data within it, you are required to create a new torrent with a new infohash. This applies not only to the files within the torrent, but also to any metadata about the torrent such as name, description, or creation date.

Another outcome is that a torrent containing large sets of files (or big individual files) will have a very large Merkle Tree and .torrent file, and might be slower to load and traverse. Data in BitTorrent is usually saved by storing the torrent metadata somewhere in application memory, and storing the files for a torrent within the filesystem. When booting up, a torrent client will typically verify all the existing data on disk to see what chunks are missing or need to be re-loaded. This means that torrent clients can account for corrupted files, and also take more time in order to verify large files.

Final Grade: A

Data Model - IPFS

IPFS also operates on Merkle Trees, but instead of grouping data together under a single infohash, it focuses on addressing each chunk of data individually. IPFS uses a data format called IPLD (Interplanetary Linked Data) which takes Merkle Trees to the next level by creating a powerful data model with different “types” and ways of traversing data. IPFS builds on top of IPLD by describing a format for data to represent files and combines it with its P2P network to publish and load files.

In contrast to BitTorrent, if two datasets in IPFS contain the same data, it’s easy to share peers between them to find and deduplicate the data. Similar to BitTorrent, IPFS datasets can be referenced using the hash of the root of their Merkle Tree, which they call the CID (Content IDentifier). In order to change any data, you need to generate and share a new CID. But unlike Bittorrent, the formats of the hashes used for CIDs are flexible and the same bit of data can use different hashes. The different hash functions and encodings are defined in the multiformats specification.

Another advantage of IPFS over BitTorrent is that large datasets can be handled by loading just the chunks needed as you traverse the Merkle DAG. For example, if you have millions of files, but only need one, you can traverse the graph just across the nodes that point to that file and ignore the rest of the dataset. However, this sparseness can be slower since you will need to wait for individual nodes along the path to be fetched from the network as you traverse the dataset.

IPFS stores data with “repositories” or “block stores” that can be configured in various formats, but these formats are typically very different from the file data they represent, making it harder to mirror an IPFS dataset directly to the filesystem. Doing so will require storing data both inside IPFS’s blockstore and on your filesystem, potentially duplicating the amount of storage necessary. Despite this drawback, the “blockstore” typically stores binary data, which represents the encoded IPLD nodes or raw buffers, so it can be very space efficient when combined with deduplication.

Final Grade: B

Data Model - Hypercore

Hypercore deviates from content addressability by using Merkle DAGs to represent an “append-only log;” i.e. you can add new blocks to the end of the log but not change any earlier ones. This log is represented using the SLEEP file format. This structure allows for easy specification of data ranges or large subsets using Bit Fields, which can reduce the data needed to tell a peer what data you have. SLEEP-based append-only logs enable you to sparsely load chunks of data from them, which is useful because you can verify that a given chunk is part of the history without needing to download the entire log.

Instead of referring to data by its root hash, Hypercore uses Public-Key Cryptography to sign the root of the SLEEP Merkle Tree. Peers store the signature along with the Merkle Tree nodes that lead to that data in order to verify individual blocks. The public keys use Ed25519 Elliptic Curves and hashing is done via the BLAKE2b hashing algorithm. The append-only log makes it easy to represent data on disk by appending to a regular file, and offers very good performance for large datasets.

On top of this append-only log abstraction, the Hypercore community uses the Hyperdrive filesystem abstraction which stores a tree of file metadata (using Hash Array Mapped Trie (HAMT) data structure). Here, each node in the “tree” is appended to the log, and individual nodes are referenced by their index within the log. This enables very fast lookup since you can exchange bitfields with remote peers to download only the subsets of the trie that you need and load just the relevant content. File data is stored in a separate Hypercore log. This allows for quickly streaming data into the log and linking to just the file ranges within the metadata log; this also keeps the metadata log smaller and faster to read.

On the downside, using multiple files per append-only log adds up quickly if you’re loading hundreds of logs because you need 4-8 file descriptors per dataset . Hypercore also suffers from the same limitations of BitTorrent in that data isn’t shared between datasets, but the tradeoff is that data within the dataset is a lot faster to discover and load. Similar to IPFS, Hypercore stores arbitrary binary data and uses encoding just for the nodes within the HAMT structure from Hyperdrive.

Final Grade: A

Data Model - SSB

SSB takes a similar approach to Hypercore in that it uses append-only logs (called Feeds) to represent data. Where it differs from Hypercore is in using JSON files (instead of SLEEP file) with “backlinks” that point to previous entries within the append-only log. Each element within a feed contains some JSON data that is signed by a user’s Public Key. Items also typically contain a type which can be used to differentiate data for things like chess from regular social-media style posts. There’s also been some work on new feed formats, but as of March 2022 things have not fully stabilized.

These messages or elements are typically traversed and processed into local databases along the lines of the Kappa Architecture for processing ordered streams of data. The local indexes are then used by applications to load data that’s relevant to them. The messages themselves are usually stored alongside the indexes within the local SSB database, rather than needing extra files to store data (like in Hypercore). The tradeoff is that you can potentially handle more feeds without running out of file descriptors, but bottlenecks in processing and verifying JSON blobs can make SSB slower anyway.

SSB feeds also don’t have the ability to be “sparse” the way other protocols can. In order to verify that the “latest” item in a feed is valid, you need to have processed the entire history and indexed all the data first. This makes the “initial sync” for SSB very lengthy before users can start interacting with the application. This does have the advantage of data being more “available” once it’s loaded, since you will have peoples’ entire feeds stored locally and won’t need to reach out to the network to load data. Since JSON isn’t the best for storing large chunks of binary data, SSB implementations also have a method of exchanging arbitrary blobs of data which are content-addressable. These blobs are referenced by peers’ feeds and typically get loaded on-demand into a local “blob store”.

Finally, SSB has plugins for storing more advanced data types like git-ssb, which the community has used to host repositories or websites that can be accessible by replicating feeds outside of the core protocol.

Final Grade: A

Mutability Overview

Mutability refers to how changeable the data is within a given P2P network, and is an important consideration if you want to update data frequently. Each protocol has a different level of support so you’ll need to carefully consider data use when selecting a protocol for your project.

Mutability - BitTorrent

BitTorrent is immutable by default, so you will need to create a new torrent and figure out side-channels for distribution. However, there’s been some work on supporting “mutable” torrents and being able to discover updates to torrents via the BitTorrent network in the form of the BEP 46 proposal. It works by using public keys to sign Distributed Hash Table (DHT) entries which contain the infohash of your latest version, and a sequence number that can enable you to discover only the latest entry. Unfortunately, major clients don’t support mutable torrents, and there are only a few minor clients that support it. Agregore (as of March 2022) has been working on making it easier to publish and load mutable torrents, and there have been efforts in the past to build applications on top of this functionality.

Even if you use BEP 46, its use of the DHT means that updates require polling for changes every now and then. In future, there might be options for replacing this with some sort of extension that will speed up initial discovery and updates. Generally, BitTorrent is useful for projects like archives where you want to download the entire dataset to disk, then make it available to other programs to use, and are okay with manual updates to the dataset.

Final Grade: D

Mutability - IPFS

From its earliest days, IPFS has incorporated mutability in the form of IPNS (InterPlanetary Name System). Initially, this worked similarly to BitTorrent’s BEP46 using public keys and a sequence number to point to an IPFS CID for your latest data. This had the same limitations of BitTorrent’s BEP46; you needed to periodically poll the DHT to find updates and it was generally prone to errors.

The latest version of IPNS makes use of an experimental Pubsub APIs. This works by creating publish/subscribe swarms of peers in libp2p that listen on the public key address and broadcast updates so that peers can be notified after an update takes place. While still requiring some experimental flags in your IPFS config,tit can drastically improve the ability to update data. Rather than waiting 30 minutes for the next DHT pool interval to happen, you can get the update in milliseconds.

Another option is to sidestep the public key cryptography entirely and use DNS TXT entries to point to CIDs using the DNSLink standard.

This has the benefit of letting users type in familiar-looking DNS hostnames like ipns://example.com rather than trying to copy long cryptic public key strings. The downside is that DNS entries typically take a while to propagate, so you can’t rely on this method if you want something faster than updates every 30 minutes.

There are a few considerations to this approach: using DNS entries makes it easier to censor an IPNS website and resolving links might not work if you can’t connect to a DNS provider on the internet; unlike public key-based IPNS, which work entirely on local DHT networks. One workaround is to point your DNSLink address to an IPNS link with PubSub enabled so that you get the readability of DNS hostnames and the speed of IPNS pubsub. Note that the support for IPNS features varies drastically between implementations, with go-ipfs being the most stable (as of March 2022).

By default, IPNS can be useful for updating something like a website where you don’t mind waiting a bit for users to get the latest version. But it can get faster if you’re willing to mess around with experimental pubsub settings. Outside of the core IPFS APIs, there’s other methods of updating data such as Textile or blockchain based approaches like ENS.

Final Grade: B

Mutability - Hypercore

Hypercore uses public keys for identifying content, and it can be very fast for getting the “latest” version of a dataset. When two peers connect to each other, they exchange information about what the latest index is for a given feed that they have replicated locally. From there, if a peer has enabled “live” mode on their connection (which is enabled by default), as soon as they get an update that’s newer than what they already had, they’ll update their direct peers about it.

This is similar to IPNS’ pubsub method of gossiping; peers that are actively replicating the data for a Hypercore are also spreading updates. Even though the append-only-log is immutable, modifying a file within a Hyperdrive can propagate quickly to other peers and is viable for distributing data in the form of JSON files.

Peers are able to easily watch() for changes at a given part in a Hyperdrive file tree and get notifications to their code when a new version is available. In my experience, Hypercore mutability has been the most reliable and fastest of the protocols described here.

Final Grade: A

Mutability - SSB

Similar to Hypercore, SSB’s public keys and active replication streams mean that data can propagate fairly quickly via peers. One difference is that the network topology of SSB relies more on central “pub” servers and “rooms’’ to discover peers, but you can generally expect data that you publish to be out and indexed by other applications within a second or two of posting it.

However, if you’re using SSB to post social data the way Manyverse and Patchwork do, you’ll need to make users aware that their posts are immutable and cannot be changed. Or else you could create a method for updating past entries that change how the post is displayed, but cannot remove the traces of the older version of the post (due to how feeds work at the moment). Similarly, blobs are immutable, so you’ll need to have a layer on top for changing pointers to a file blob in the same vein as git-ssb. SSB mutability works in tandem with the sorts of applications you build on top and can work for cases where you’re periodically pulling updates or have near-real time interactions (such as SSB Chess).

Final Grade: A

Next up, the third post in this series, covering peer discoverability and security.