For the past few years Hypha members have been tracking and contributing to Polis. Polis is a tool for gathering and displaying what groups of people think, and we’ve been exploring the emerging civic processes that make use of it. As technologists, we’ve been disillusioned by how economies of capital and attention distort our tools. Polis feels like a tool that has largely evaded the pull of these forces. Unlike other tech platforms, the conversations it generates are rich and nuanced. And while founded as a US startup, Polis is now an open source tool stewarded by the non-profit Computational Democracy Project.

We came across Polis in 2016, while following some civic developments that had spun out of Taiwan’s popular student-led Sunflower Movement two years prior. At this time it was being used by the Taiwanese civic tech community to conduct a process of participatory democracy at scale as part of vTaiwan. We were excited to see how a tool like Polis, when wrapped in a thoughtful process, enabled a way for participants to navigate the complex social fabric of democracy in a small country and have real impact. We won’t duplicate the writing and research (including by one of our members) on these processes and movements here.

So what’s it like to use?

Polis wraps clever math techniques (advanced statistics and machine learning) in a friendly user interface in order to help people see and listen to one another while navigating complex topics. It isn’t a decision-making tool on its own, but rather a decision-supporting tool for mapping the landscape of opinions. It is particularly well-suited to divisive topics for which there is no clear path forward.

Let’s pretend you’re a participant in a civic process that’s using Polis. You get a link to something you vaguely remember hearing about. You click the link and see a lot of text at the top, you mostly don’t read it because you’re a normal person. Below that, you notice a statement and some buttons for agreement or disagreement.

You press agree and another statement replaces it. You continue to agree to some statements, or disagree with others. For those you don’t feel strongly about, or don’t understand, you pass. Maybe you submit a better-phrased version below.

After you respond to a few statements, you notice a blue dot amongst some larger grey blobs in the visualization below the buttons you’re clicking. After each button-click the dot moves around a bit and slowly migrates into the middle of one of the blobs.

You click the blob that the dot is within. It’s highlighted and you see statements appear which you can flip through. These statements have claims of high levels of agreement and disagreement and are all ones that match your own views. You realize that the dot represents you, and this blob is the group of people who predominantly share your opinions: this is your blob!

Clicking the other blobs, you understand these are other groups whose shared opinions you can explore.

Soon, you notice another button below the visualization: Majority Opinion. You click it and are presented with more statements, but these are ones that everyone has high agreement and disagreement on. Crucially, these are the statements that a majority of participants are in alignment on, regardless of any strong differences that exist between groups. These majority opinions are an important leverage point that processes involving Polis make use of, and something we’ll discuss in future writing.

For more on the initial participant experience, one of our members has created an introductory video in collaboration with fellow Polis contributors.

No new facilitation under the sun

It’s easy to talk about a tool like Polis as something new under the sun. But in truth, Polis is only providing another mechanism to represent intuitions that skilled facilitators already know how to surface. As social creatures we do basic forms of facilitation with each other all the time. However skilled facilitators often can read a group and identify the factors underpinning agreements and disagreements. They can help a group see their collective self more clearly. Polis democratizes facilitation. It helps everyone to see the larger group dynamics that facilitators see. Crucially, it also supports investigating these dynamics in an online space, where subtle social signals and body language cues are missing.

At it’s best (when embedded in a process), Polis can open up these facilitator skills to everyone, even the 12 year-old who sets it up in 5 minutes to plan a Dungeons & Dragons league. Just as there are many ways to poorly facilitate in person, there are ways to misuse Polis, for example through poorly framed questions or a lack of representative seed statements from the moderator. However, as with in person facilitation with bodies and body language, Polis supports participants “failing toward success”: if participants keep trying, the group often eventually stumbles toward better understandings of its deep stories. In these cases, the benefits are distributed among participants and the tool provides room for emergence, as any participant can rise up to facilitator if the process goes off track. We’ll touch more on the ways Polis can help with developing collective stories in a future post.

Building careful consensus

One of the key elements of Polis embedded in processes is the way that it encourages consensus in seemingly divided publics, or gives shape to unrecognized groups of people around topics. These abilities are valuable especially when multiple parties are negotiating complicated issues, based on closely held values and vastly different experiences. Difficult deliberations can feel full of tension and finding an outcome that works for everyone can seem hopeless. However, they also cannot last: at some point the situation has to come to an end whether there is a satisfying conclusion or not.

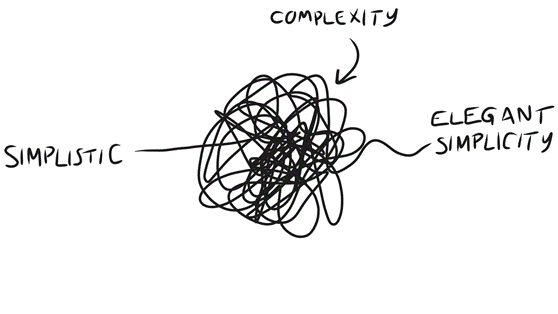

When there isn’t a conclusion that all can agree on often there is a retreat to existing camps and simplistic narratives of what happened. Critically, simple stories might feel true for one group, but not others. These stories lack the nuance to contain what’s dear to all parties. Polis as a tool seems better able to provide the spaces to listen well and speak to our closely held values. It’s able to produce stories that all sides can accept and see themselves in. We’ll cover how the consensus-building mechanisms of Polis lead to forms of elegant simplicity that respond to complex issues in the future.

What’s next?

It’s our belief that Polis lays the groundwork for processes that may one day complement and support some of our established democratic tools: public consultations, elections, and deliberative assembly. We’re excited to work with Polis to run online-offline consultations, bridge real-time and async audiences, repair community fractures after ugly and complex interactions (e.g., mailing list flame-outs), and help map ecosystems. In the coming months, we’re planning to explore the ideas we touched on above in Dripline. If you’d like to learn more in the meantime, you can join the Conversa Polis User Group weekly open calls or anytime chat (currently stewarded by Patcon, a Hypha member-worker).